In a Watched City: The Baltimore Black Panther Party

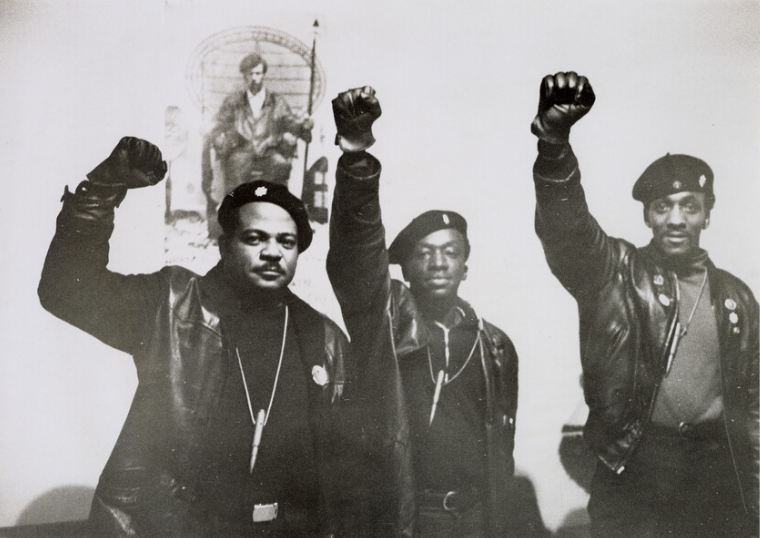

The Baltimore Black Panther Party was founded in 1968 by Warren Hart, a figure who would later be revealed as an informant for the F.B.I. and the National Security Agency. He not only surveled them, he also encouraged them to commit crimes. His exposure began as Marshall “Eddie” Conway” and other Panthers began to notice discrepancies. Hart was the first of many informants. Baltimore’s Panthers operated under intense scrutiny from the outset. When Hart fled, he was replaced by John Clark, who was regularly harassed and jailed. Steve McCutchen, who was about 19 at the time of joining the Panthers, was lieutenant of information and supported efforts to get Clark released, until he himself was jailed.

Because Maryland law prohibited the open carrying of firearms, the Baltimore chapter never adopted the armed police patrols that became synonymous with the Panthers elsewhere. Instead, they turned inward, embedding themselves deeply in neighborhood life. They organized free breakfast and lunch programs at Martin de Porres Catholic Church, feeding up to two hundred children a day. They opened a free medical clinic staffed by volunteer doctors and nurses from Johns Hopkins. They escorted sick residents to social-services offices, intervened in eviction cases, and even offered a free dry-cleaning service.

The Baltimore Panthers built an organization that looked less like a paramilitary outfit and more like a mutual-aid society under siege. The membership was overwhelmingly working class—high-school graduates employed in the city’s service and industrial sectors. Paul Coates, who started off as a community volunteer at the age of 22, after serving nineteen months in Vietnam – later became a member and co-founded the George Jackson Prison Movement.

The intention was twofold to develop a jobs program for returning citizens and provide books –many out of print and hard to acquire – to folks in prison. VP of Baltimore Brothers, Bilal Rahman recalls,

“that's my first job. When I came home,.. Yeah, I'm a printer by trade. I got that trade out of prison, came home and started printing all his books down there. Yeah, yeah, definitely. I met so many authors… Paul Coates was my first boss at Black Classic Press. I was referred to him by my mentor, Eddie Conway,...He mentored me for years while I was incarcerated, and he knew that I worked in the printing shop while we was incarcerated, so he referred me to Paul Coates so that I could actually get down there. And, you know, print books with him, one of the best jobs that I had.”

While this aspect of the effort was short-lived, The Black Book – later to become Black Classic Press, has left a living legacy right here in Baltimore, a Black-owned publishing company that has printed over 4 million books by Black authors world wide.

The party held regular political-education classes. Children attended “liberation lessons,” learning Black history and political consciousness alongside basic skills. To J. Edgar Hoover and local police, these programs were evidence of indoctrination; to parents, they were often the only reliable source of food, care, and affirmation available.

The Panthers persisted, extending their organizing into labor struggles, including efforts to unionize incarcerated workers and to support Black employees at the Social Security Administration. They operated alongside a constellation of other reformist spaces—the Peace Action Center, Viva House, the federally funded Model Cities program—each attempting, in its own way, to address the failures of the urban state.

The Baltimore Black Panther Party disbanded in 1972. By then, many of the Panthers’ initiatives had either been absorbed by nonprofits or extinguished by austerity and repression.

Baltimore’s Panthers complicate the easy narratives. They were neither reckless radicals nor romantic revolutionaries. They were pragmatic idealists, adapting to legal constraints, financial scarcity, and relentless surveillance while insisting that political struggle begin with feeding children and keeping neighbors housed.

Their story is a reminder that grassroots movements are most vulnerable where they are most necessary and that the state’s gaze has often been sharpest when Black communities attempt to govern themselves. For organizers today, working without the insulation of wealth or patronage, Baltimore’s Panthers offer both a model and a warning: that meaningful change is built locally, sustained collectively, and contested at every step.